Batch Recipe Execution

This topic is part of the SG Systems Global manufacturing execution, inventory integrity and batch traceability glossary.

Updated December 2025 • batch recipe execution, ISA-88 style procedures, master recipe vs control recipe, step sequencing, parameter enforcement, electronic work instructions, eBR/EBR readiness, equipment preconditions, hold points, electronic signatures, exceptions & deviations, audit trails, Part 11/Annex 11 data integrity, BRBE, yield and mass balance • Pharmaceutical, Dietary Supplements, Food Processing, Ingredients & Dry Mixes, Cosmetics, Agricultural Chemicals, Plastic Resin, Consumer Products, Bakery, Sausage & Meat Processing, Produce Packing, Medical Devices

In process and batch manufacturing, Batch Recipe Execution is where “the approved way” becomes “the way it actually happened.” It’s the operational discipline of running a batch by an approved set of procedural steps—sequenced, parameterized, time-stamped, and controlled—so every critical action is performed in the right order, with the right materials, under the right conditions, with the right evidence.

That sounds obvious until you look at how many plants still operate on tribal knowledge, paper binders, disconnected spreadsheets, and controller programs that nobody wants to touch because “it works.” Then something changes: a supplier lot shifts potency, a new operator starts, a line is swapped, a parameter is “tweaked just this once,” or an auditor asks you to prove the batch followed the approved procedure. That’s when the gap shows up.

At SG Systems Global, we treat Batch Recipe Execution as the center of gravity for modern manufacturing control. It ties your Products & Formulas and BOM to real execution—where operators verify identity, weigh and dispense, charge vessels, run holds, complete in-process checks, manage rework, and close the record with defensible evidence. And it’s inseparable from Recipe & Parameter Enforcement, Work Order Execution, and exception governance via Deviation Management.

Here’s the blunt truth: if your plant can’t prove step-by-step execution with time-stamped, attributable events, then “recipe execution” is just a story you tell after the fact. That story might pass on a quiet day. It won’t hold up when the day is not quiet.

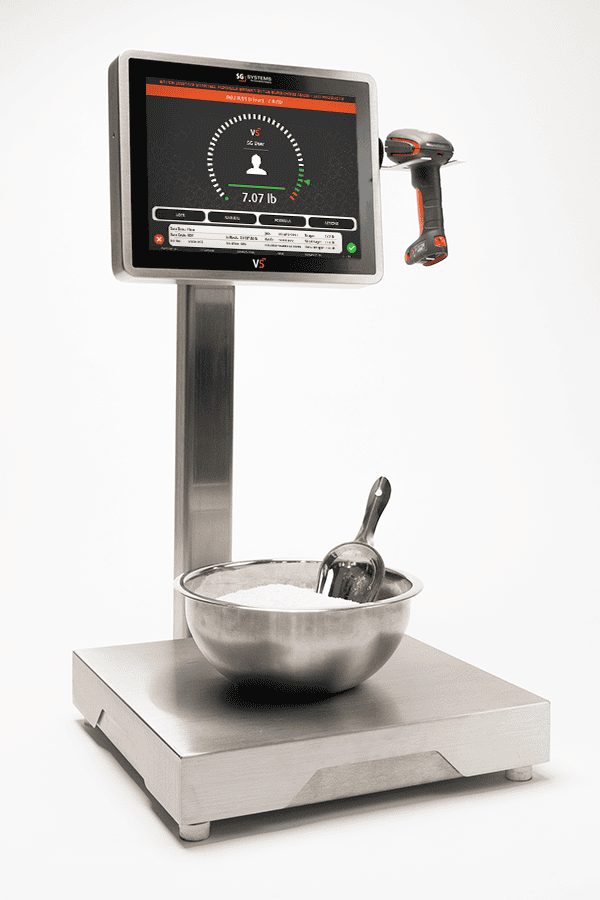

Figure: Batch recipe execution becomes audit-ready when procedural steps, setpoints, confirmations, and exceptions are captured as structured, time-stamped events—not as end-of-shift summaries.

When batch recipe execution is designed correctly, you get four outcomes that matter in the real world:

- Right-first-time execution. The system guides operators through the approved sequence and prevents “creative shortcuts” that become deviations later.

- Regulatory defensibility. You can produce a coherent, complete execution record aligned with 21 CFR Part 11 and Annex 11 expectations, with a complete Audit Trail.

- Faster investigations and release. Structured step events and exceptions enable Batch Review by Exception instead of manual reconstruction.

- Operational clarity. You can see where time is lost, where parameters drift, where holds occur, and why yield or quality shifts—because the procedure and the evidence are linked.

“A batch recipe isn’t a PDF. It’s a controlled sequence of decisions. If you can’t show the decisions—who made them, when, and under what limits—you didn’t execute a recipe. You improvised.”

1) Batch recipe execution stack — what must be connected

Batch Recipe Execution is not one screen and not one “start batch” button. It’s a stack of master data, workflow logic, equipment context, data capture, and governance. If any layer is weak, execution degrades into paper, guesswork, or uncontrolled overrides.

| Layer | What it controls | Key glossary / system anchors |

|---|---|---|

| Product, Formula & BOM | Approved material list, targets, tolerances, UoM rules, substitutions |

Products & Formulas, BOM |

| Procedure / Recipe Model | Step structure, sequencing, phase logic, hold points, required checks |

Recipe & Parameter Enforcement, Work Order Execution |

| Equipment Context | Which vessel/line is used, readiness, clean status, equipment interlocks |

Hard Gating, Audit Trail |

| Material Identity & Lot Control | Right item/right lot verification at dispense and charge; status enforcement |

Material Identity Confirmation, Material Lot Assignment, Hold/Release |

| Execution Data Capture | Prompts, confirmations, e-sign, instrument capture, in-process results |

Weigh & Dispense Automation, Barcode Validation |

| Consumption & Yield Logic | Actual usage vs theoretical, mass balance, yield reconciliation, rework/scrap |

Material Consumption Recording, Batch Yield Reconciliation |

| Exceptions & Quality Governance | Deviations, nonconformances, approvals, CAPA linkage, release constraints |

Deviation Management, Nonconformance Management |

| Review & Record Closure | EBR readiness, exception review, signatures, record completeness checks |

BRBE, Data Integrity |

2) Why batch recipe execution is a high-stakes control (not a documentation preference)

Plants don’t get in trouble because they “forgot to write something down.” They get in trouble because the process was not controlled tightly enough to prevent or surface risk in the moment. Recipe execution is where that control either exists—or doesn’t.

Batch recipe execution is high-stakes because it governs the things that cause the biggest real-world problems:

- Sequence-dependent quality. If order matters (and it often does), step skipping or reordering can create invisible defects.

- Parameter sensitivity. Time, temperature, mixing energy, vacuum, pressure, feed rates, and hold durations can make or break a batch.

- Material identity and lot genealogy. A perfect receiving record is meaningless if the wrong lot is charged into the batch.

- Exception reality. Every plant has exceptions. A mature plant governs them. An immature plant hides them in notes and “adjustments.”

- Defensible release. If you claim controlled execution, the record must show controls in action—especially around overrides and deviations.

Recipe execution is also where the plant’s culture shows up in data. If people routinely bypass steps, override limits, or do “paper later,” the system will either expose it (good) or allow it (bad). The goal is not to punish operators. The goal is to build a workflow where the easiest path is the compliant path.

3) What “recipe” means (and why plants confuse it with a formula)

Many organizations use “recipe” to mean “ingredients and quantities.” That’s only part of it. In batch manufacturing, a complete recipe has two components:

- The formula: what materials, what targets, what allowable ranges (often captured in Products & Formulas and BOM).

- The procedure: how the batch is executed step-by-step—sequence, parameters, holds, checks, and approvals.

Batch Recipe Execution is primarily about the procedure, not just the ingredient list. It answers: What is the next step? What must be true before we proceed? What must we capture? What limits apply? What happens if something goes wrong?

In mature systems, the procedure is structured (often aligned to ISA-88 concepts), which makes it executable instead of interpretive. Even if you don’t use ISA-88 terminology, the logic is the same: a batch has phases, operations, and steps that must be followed, measured, and evidenced.

The key “tell it like it is” point: if the procedure is stored in a PDF and interpreted by humans under time pressure, your execution is variable by design. If the procedure is implemented as a controlled workflow with enforced parameters and gated confirmations, your execution becomes consistent—and your record becomes defensible.

4) Execution modes: manual, guided, semi-automated, and fully automated

Not every plant needs the same level of automation. But every plant needs control. In practice, batch recipe execution typically falls into one of these modes:

- Manual with paper SOP. Operators execute from binders. Data is handwritten and later transcribed. This is simple, but data integrity risk is high and review is slow.

- Guided electronic execution. The system provides step-by-step instructions and captures confirmations, results, and signatures. This reduces ambiguity and creates structured records.

- Semi-automated execution. The system guides operators and also integrates instruments/equipment (scales, sensors, PLC signals) to capture data automatically and enforce limits.

- Fully automated batch control. The controller executes most steps automatically with operator interventions at defined points (materials, samples, approvals). This is powerful, but only when change control, validation, and integration discipline are mature.

There is no prize for “most automated.” The right target is the level of automation that matches your risk and process variability. High-risk steps (critical additions, allergen controls, actives, potency adjustments) should be tightly controlled. Low-risk steps can often be guided without heavy integration.

What matters is that your execution model is explicit. If you can’t explain where you rely on automation vs human confirmation—and what gates protect each—your control strategy is accidental.

5) The minimum structure your recipe execution must have to be defensible

If you want recipe execution that supports real operations and holds up under scrutiny, you need a structured model for steps and events. At minimum, your execution recipe should define:

- Recipe identity: recipe name/ID, version, effective dates, approved status, linked product(s).

- Batch context: work order/batch number, target quantity, unit of measure, equipment/line assignment.

- Step list: ordered steps with unique IDs (not “Step 7a scribbled in the margin”).

- Preconditions: what must be true before the step can start (equipment ready, materials staged, QA release, training requirements met).

- Actions: what the operator/system must do (add material, mix, heat, sample, hold, transfer, package).

- Parameters: setpoints and ranges (time, temperature, speed, pressure, weights, counts) with tolerance logic.

- Required data capture: what must be recorded (instrument reading, scan, pass/fail check, observation).

- Hold points: where execution must pause pending QA or supervisor approval.

- Exception paths: what happens when a limit is breached, a scan fails, a component is unavailable, or a rework loop is required.

- Signatures & roles: who can perform and who can approve critical steps (UAM).

- Audit trail: secure record of changes and overrides (Audit Trail).

This isn’t “extra bureaucracy.” It’s what prevents the classic failure: a batch record that exists but cannot answer basic questions about what really happened.

6) Recipe version control: where plants quietly lose control

Recipe execution is only as good as recipe governance. A shocking number of plants run “Version 3” on paper, “Version 4” in a spreadsheet, and “Version 2” in a PLC—then argue about which one is approved. That is a control failure, not a documentation issue.

A defensible recipe execution program requires:

- Single source of truth. One approved recipe version per product/process, with a clear effective date.

- Controlled changes. Recipe edits are managed through Management of Change, not informal “tweaks.”

- Impact awareness. When a parameter changes, the system knows which steps, equipment, validations, and training are affected.

- Traceability. Every batch is linked to the recipe version used—so investigations don’t become archaeology.

- De-risked rollout. New versions can be tested, staged, and deployed without “surprise” changes mid-shift.

If operators can edit targets on the fly without reason and approval, you don’t have a recipe. You have suggestions.

7) Parameter enforcement: the difference between guidance and control

Batch recipe execution must decide what the system will enforce vs what it will merely display. This is where plants either gain control or create theatre.

Recipe & Parameter Enforcement is where you define what “acceptable execution” means. Common parameter enforcement patterns include:

- Hard limits. The system blocks progress until the parameter is within range (e.g., temperature must be between X and Y before mixing step starts).

- Soft limits with documented justification. The system warns and requires a reason/approval if exceeded.

- Dynamic scaling. Targets adjust based on batch size, potency, concentration, or yield corrections—but the logic is controlled and traceable.

- Time and sequence enforcement. Steps cannot be completed out of order unless a governed exception path is executed.

Parameter enforcement also requires ruthless discipline on units and conversions. If the recipe is in kg, the scale reads in g, and the operator “converts mentally,” you are inviting silent 10× errors. Enforcement means the system does the math, records the basis, and flags anomalies.

The hard lesson: “We display the target” does not equal control. Control means the system can prevent the wrong outcome or force the right documentation when the wrong outcome happens.

8) Equipment readiness, line clearance, and preconditions: don’t start a batch into chaos

Recipe execution starts before the first material is added. If you allow a batch to start when the wrong vessel is assigned, the previous product residue is still present, or the line clearance is incomplete, you’re manufacturing a deviation by design.

Robust batch recipe execution defines preconditions such as:

- Equipment assignment. The batch is bound to the approved equipment set (vessel, line, filler) or a controlled alternative.

- Clean/ready status. Required cleaning steps are completed; status is visible and enforced (where applicable).

- Calibration/verification. Critical instruments (scales, sensors) are in qualified status.

- Material availability. Required materials are staged and in correct quality status (released, not hold).

- Personnel readiness. The operator has the role/training to execute and sign required steps.

This is where hard gating is not a buzzword—it’s a cost-saving control. Every “start anyway” you prevent is a rework, scrap, or investigation you don’t have to do later.

9) Material additions inside recipe execution: identity, lot, and consumption must be step-linked

In most batch environments, the highest-risk moments are material additions—especially critical actives, allergens, concentrated additives, or micro-ingredients. Batch recipe execution should treat material additions as controlled steps with enforced evidence, not as narrative entries.

A mature model uses:

- Identity verification. The right item and right lot are confirmed (Material Identity Confirmation).

- Lot assignment rules. Lot selection follows defined rules (FEFO, directed lot, approved swap logic) via Material Lot Assignment.

- Status enforcement. Materials in quarantine/hold cannot be consumed (Hold/Release).

- Weigh/dispense capture. Weights are captured from instruments where possible (Weigh & Dispense Automation).

- Consumption as a transaction. Actual usage is recorded as structured events within the step (Material Consumption Recording).

When these are step-linked, the batch record becomes explainable: you can see exactly which lots were used at which procedural moment. When they are not step-linked, you get “consumed 50 kg sometime during the batch,” which is not traceability—it’s accounting.

10) In-process checks, sampling, and holds: execution must include the “stop points”

In many industries, the procedure includes in-process checks: pH, viscosity, moisture, density, torque, appearance, metal detection, sieve checks, label verification, or fill-weight checks. These are not optional checkboxes. They are control points.

Batch recipe execution should define:

- When checks occur. Step-linked timing (e.g., “after mixing for 10 minutes, take sample”).

- What limits apply. Acceptable ranges and what happens if the result is out of range.

- Who can approve disposition. Role-based approvals and signatures where required.

- Hold behavior. Whether the batch pauses pending results and how long it can remain on hold.

This is where plants get into trouble if they treat holds as informal. If a batch sits on hold and operators still make additions “to save time,” you’ve broken the procedural chain. A controlled system makes the hold state visible and enforceable.

11) Exceptions are normal. Uncontrolled exceptions are the problem.

No recipe survives contact with reality without exceptions: a material is short, a parameter drifts, a piece of equipment alarms, a sample fails, or an operator makes a mistake. The difference between mature and immature manufacturing is not whether exceptions happen—it’s whether exceptions are governed.

Batch recipe execution must include explicit exception paths, such as:

- Reweigh / remeasure. Corrective actions within defined limits.

- Substitution workflow. Approved alternatives with documented approvals.

- Parameter override workflow. When limits can be exceeded, who approves, and what reason code is required.

- Rework loops. Defined steps for adding rework lots back into a batch (with identity and status control).

- Scrap events. Documented removal, reason, and approval so yield variance is explainable.

- Deviation routing. When an exception becomes a formal deviation or nonconformance.

The key principle: the system should not force people to “hide reality” to keep the batch moving. If the only way to proceed is to bypass controls or backfill paperwork, the workflow is badly designed. Exception paths must be practical, fast, and governed—or people will route around them.

12) Data integrity and audit trails: recipe execution must be evidence, not editable narrative

Recipe execution creates the execution record. In regulated manufacturing, that record is only valuable if it is trustworthy. That requires:

- Attribution. Unique users, no shared logins, roles aligned to responsibilities (UAM).

- Contemporaneous capture. Events recorded at the moment they happen, not hours later.

- Secure audit trails. Edits, overrides, and configuration changes are time-stamped and visible (Audit Trail).

- Controlled electronic signatures. Approvals have meaning and are linked to the record (especially for holds, overrides, and critical steps).

- Record completeness checks. Missing steps, missing scans, missing results are treated as exceptions, not “we’ll fix it later.”

It’s worth saying plainly: if operators can “edit the record until it looks right,” your recipe execution record is not evidence. It’s a polished narrative. Regulators and customers will treat it that way.

13) Yield, mass balance, and closure: execution must reconcile to reality

A batch recipe doesn’t end when the last step is completed. It ends when the record closes cleanly: materials consumed match what was recorded, output quantity is explained, rework and scrap are accounted for, and the batch can move forward with confidence.

This is where Batch Yield Reconciliation and consumption controls intersect with recipe execution. Practical closure questions your system should answer quickly:

- Actual vs theoretical. Which components exceeded tolerance and why?

- Unplanned additions. Were any non-BOM items added? What authorized it?

- Missing evidence. Are there any steps with missing confirmations, scans, or results?

- Hold resolution. Were holds released appropriately with approvals?

- Rework/scrap accounted. Are rework lots and scrap events recorded and approved?

This is the foundation of BRBE. When execution data is structured and validated, review becomes targeted and fast. When execution data is narrative and loose, review becomes slow and subjective.

14) Industry realities: same control, different pain points

Batch Recipe Execution exists across industries, but the risk drivers differ. Your execution design should reflect what can hurt you most.

Pharmaceutical Manufacturing (industry overview): step sequence and controlled evidence are central to batch release defensibility. Recipe execution must support electronic records expectations (Part 11, Annex 11) with strong exception governance and audit trails. “We followed the SOP” needs proof, not confidence.

Dietary Supplements (industry overview): micro-ingredient dosing, blend uniformity, and label claim sensitivity make recipe enforcement critical. Guided execution with weigh/dispense control prevents quiet dosing drift and reduces potency-related surprises.

Food Processing (industry overview): recipe execution supports allergen control, traceability, and recall readiness. Sequence and identity control matter because the cost of ambiguity is often an over-recall that burns margin.

Ingredients & Dry Mixes (industry overview): batching powders amplifies loss, rework loops, and parameter sensitivity (mix time, order of addition). Execution records help separate real process loss from uncontrolled handling.

Cosmetics Manufacturing (industry overview): consistency and complaint investigations depend on being able to prove which process version and parameters were used. Execution prevents “works on shift A but not shift B” variability.

Agricultural Chemical Manufacturing (industry overview): potency corrections and hazardous material handling increase the need for controlled approvals and strong exception routing. Recipe execution becomes both a safety and compliance control.

Plastic Resin Manufacturing (industry overview): bulk handling and additive dosing can be automated, but recipe execution still needs controlled setpoints, traceable lots (where applicable), and exception evidence when equipment drifts.

Consumer Products (industry overview): high SKU variety means more changeovers, more opportunity for wrong settings, and more need for enforceable procedural discipline—especially where packaging and labeling are involved.

Bakery Manufacturing (industry overview): variability is constant. Recipe execution creates consistency by capturing actual parameters and making deviations visible rather than normalized.

Sausage & Meat Processing (industry overview): catch-weight realities and raw input variability demand accurate step capture and real weights. “Standard time/standard usage” assumptions collapse quickly in this space.

Produce Packing (industry overview): execution often includes label control, inspection points, and packaging usage. Controlled step capture protects against disputes and supports order integrity.

Medical Devices (industry overview): device history record readiness depends on controlled procedures, traceable components, and governed rework. Recipe execution must capture what was done and why exceptions occurred.

The unifying theme: the more the process outcome depends on sequence, parameters, and identity, the less tolerance there is for “people will remember.”

15) System architecture: MES + automation + QMS (and why “just ERP” doesn’t cut it)

Batch recipe execution is fundamentally a manufacturing execution problem. ERP systems are excellent at financial and inventory posting, but they are not designed to enforce step-level execution with real-time gating on the shop floor.

A modern architecture typically looks like this:

- MES defines and executes the recipe steps, enforces parameters, captures evidence, and creates the execution record.

- Automation (PLC/SCADA) runs equipment-level control loops and provides real signals (temperatures, times, alarms, states).

- WMS supports lot/location truth and staged material control where warehouse discipline is required.

- QMS governs deviations, nonconformances, CAPA, and training so exceptions are handled explicitly and consistently.

- ERP receives production and inventory outcomes for planning and financial posting, but it should not be the primary evidence system for execution.

Recipe execution becomes defensible when these layers share consistent master data (items, lots, equipment IDs), consistent time, and consistent governance. If you treat each system as an island, your “recipe execution” will be stitched together manually—exactly when you can least afford manual work.

16) How V5 implements batch recipe execution in practice

SG Systems Global’s V5 platform implements Batch Recipe Execution as controlled, step-driven execution across MES, WMS, and QMS—so the recipe is executed as a workflow, not recorded as an after-the-fact report.

- V5 MES. The V5 MES layer:

- Executes batch steps tied to work orders, enforcing sequencing where required.

- Applies recipe & parameter enforcement for setpoints, ranges, and targets.

- Captures structured evidence: confirmations, results, timestamps, and approvals with full audit trail support.

- Enforces identity and scanning rules via barcode validation for critical additions and container IDs.

- Supports consumption capture and genealogy through step-linked events (material consumption recording).

- Enables exception-driven review aligned with BRBE.

- V5 WMS. The V5 WMS layer:

- Supports directed lot selection and staged/kitted material control where needed.

- Improves inventory accuracy by keeping lot/location truth aligned to execution events.

- Strengthens FEFO and status-based availability logic (FEFO, Hold/Release).

- V5 QMS. The V5 QMS layer:

- Routes recipe execution exceptions into governed workflows (deviations, nonconformances) instead of hidden “adjustments.”

- Supports structured investigations and CAPA linkages so recurring execution failures are addressed structurally.

- Aligns access and approvals to roles and training governance (UAM).

- V5 Connect API. The V5 Connect API:

- Integrates scales, scanners, label printers, and shop-floor devices to reduce manual entry and strengthen evidence capture.

- Supports reliable event capture so recipe execution data is contemporaneous and reviewable.

Implementation note: V5 doesn’t treat “recipe execution” as a narrative document. It treats it as executable logic with enforceable steps and measurable exceptions—so review and improvement become systematic.

For a broader overview of the platform layers, see V5 Solution Overview and the industry hub at Industries.

17) KPIs that prove recipe execution is working (or expose that it isn’t)

Recipe execution is measurable. If you’re not measuring it, you’re running on anecdote. Practical KPIs include:

- Step adherence rate. % of batches completed with no step skips or out-of-sequence events.

- Override rate. Count of parameter overrides per batch or per 100 steps (trend by line and shift).

- Manual entry rate. % of critical values typed vs captured electronically (should trend toward near-zero for criticals).

- Exception density. Exceptions per batch by category (materials, parameters, equipment, holds).

- Hold time. Total hold duration per batch; time-to-release for hold points.

- Cycle time variability. Variation in batch duration by recipe version and equipment set.

- Right-first-time (RFT). Batches released without deviation or rework events (with honest criteria).

- Consumption variance. Actual vs theoretical by component and step (yield reconciliation link).

- BRBE effectiveness. % of batches reviewed via exceptions only; batch review closure time.

- Repeat deviation rate. Recurrence of the same recipe execution deviation after CAPA closure.

If you can’t quantify these, you’re not controlling execution—you’re hoping your procedures are being followed.

18) Common pitfalls: how plants sabotage batch recipe execution

- Recipes stored as PDFs. Humans interpret; interpretation varies; evidence is weak.

- “We’ll document later” culture. Late entries destroy contemporaneous evidence and create audit pain.

- Uncontrolled parameter tweaks. “Small changes” without governance become big drift over time.

- Weak unit conversions. UoM inconsistency creates silent errors that only show up in yield or QC failures.

- Scanning without enforcement. If wrong-lot scans don’t block or route exceptions, scanning becomes theatre.

- Exceptions too hard to log. If deviation routing is painful, people will route around it.

- No step context for data. Recording results without linking them to a step makes investigations slow and ambiguous.

- Disconnected quality status. Materials on hold still get used because the system doesn’t enforce status.

- Line/equipment ambiguity. If you can’t prove which vessel/line executed which step, traceability collapses.

- Recipe version confusion. Multiple “approved” versions in circulation is a control failure.

19) Quick-start checklist: strengthening batch recipe execution in 30–60 days

- Identify your highest-risk recipe families (actives, allergens, micro-ingredients, hazardous materials, critical parameters).

- Define what “step adherence” means in your plant (what can be flexible vs what must be enforced).

- Standardize recipe structure: steps with IDs, clear preconditions, clear data capture requirements.

- Choose which steps require hard gates (wrong-lot, hold status, OOT parameters, missing checks).

- Make identity verification non-negotiable for critical additions (identity confirmation).

- Ensure materials on hold/quarantine cannot be consumed (hold/release enforcement).

- Implement step-linked consumption capture for key components (consumption recording).

- Integrate scales and scanners where possible so weights/scans are captured, not typed (V5 Connect API).

- Define reason codes and approval paths for overrides (keep them realistic and limited).

- Route real exceptions into deviation management workflows instead of hiding them.

- Lock recipe versions: one approved version per effective period; changes through MOC.

- Define “paper fallback” rules: when allowed, who approves, and how it’s captured in the record with audit trail evidence.

- Implement record completeness checks before batch closure (missing scans, missing steps, unresolved holds).

- Adopt BRBE logic early—review exceptions, not everything.

- Track the KPIs above weekly and act on them (override rate, manual entry, hold time, repeat exceptions).

20) Batch Recipe Execution FAQ

Q1. Is a formula the same as a batch recipe?

No. A formula defines what materials and targets you intend to use. A batch recipe includes the procedural execution: step sequence, parameters, hold points, checks, and approvals. Formula without procedure is not executable control.

Q2. Do we need full automation to have strong recipe execution?

No. Guided electronic execution with hard gates on critical steps often delivers most of the benefit. Full automation helps when processes are stable and integration discipline is strong, but control is possible without it.

Q3. How granular should recipe execution be—high-level phases or step-by-step?

Base it on risk and variability. Critical additions, allergen controls, actives, and sensitive parameters should be step-level with enforced evidence. Low-risk activities can be phase-level with confirmations and required results captured. If a mistake is expensive, make it impossible or loudly exception-based.

Q4. How do we handle “real-world” changes during a batch?

Through governed exception workflows: substitutions with approvals, parameter override with reason code and signature, rework loops with identity and status control, and deviation routing where required. If changes happen “off the record,” your control strategy is broken.

Q5. Can ERP handle batch recipe execution by itself?

ERP can post results. It is not designed to enforce step-level execution with real-time gating, scan validation, instrument capture, and structured exception handling on the floor. For defensible execution, you need MES-level workflow control.

Q6. What do auditors want to see in batch recipe execution records?

They want consistent evidence that the approved procedure was followed: clear link to recipe version, step-level timestamps, identity verification where required, parameter limits and outcomes, approvals for exceptions, and a complete audit trail showing changes and overrides. If the record is editable until it looks right, it won’t hold up.

Related Reading

• Industries: Industries Hub | Pharmaceutical Manufacturing | Dietary Supplements | Food Processing | Ingredients & Dry Mixes | Cosmetics | Agricultural Chemicals

• Products: V5 MES | V5 WMS | V5 QMS | V5 Connect API | V5 Solution Overview

• Glossary: Batch Recipe Execution | Work Order Execution | Recipe & Parameter Enforcement | Material Consumption Recording | Weigh & Dispense Automation | Hard Gating | Batch Yield Reconciliation | BRBE | Data Integrity | Audit Trail

OUR SOLUTIONS

Three Systems. One Seamless Experience.

Explore how V5 MES, QMS, and WMS work together to digitize production, automate compliance, and track inventory — all without the paperwork.

Manufacturing Execution System (MES)

Control every batch, every step.

Direct every batch, blend, and product with live workflows, spec enforcement, deviation tracking, and batch review—no clipboards needed.

- Faster batch cycles

- Error-proof production

- Full electronic traceability

Quality Management System (QMS)

Enforce quality, not paperwork.

Capture every SOP, check, and audit with real-time compliance, deviation control, CAPA workflows, and digital signatures—no binders needed.

- 100% paperless compliance

- Instant deviation alerts

- Audit-ready, always

Warehouse Management System (WMS)

Inventory you can trust.

Track every bag, batch, and pallet with live inventory, allergen segregation, expiry control, and automated labeling—no spreadsheets.

- Full lot and expiry traceability

- FEFO/FIFO enforced

- Real-time stock accuracy

You're in great company

How can we help you today?

We’re ready when you are.

Choose your path below — whether you're looking for a free trial, a live demo, or a customized setup, our team will guide you through every step.

Let’s get started — fill out the quick form below.